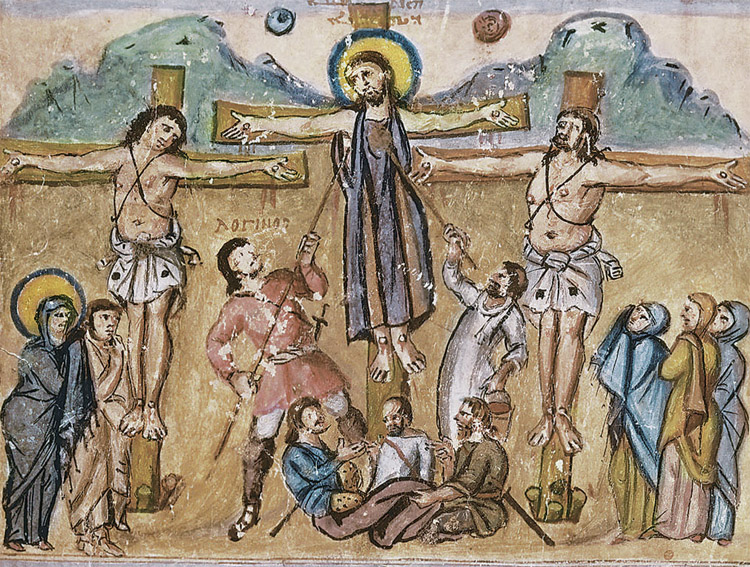

In these and most other Crucifixions before the 13th century, Christ's body does not sag on the cross. Unambiguously alive, he faces forward and extends his arms straight out as if in exultation. This seems consonant with the emphasis on his divinity. Above him images of the sun and moon signify his "cosmic sovereignty."2

The same iconography can be seen in crucifixes of this period. See this section of our study of crosses and crucifixes.

SECONDARY FIGURES IN THE IMAGES

In the Syriac illustration the cross is flanked by a man on the right proffering the vinegar sponge and a soldier on the left piercing Christ's side.3 The soldier is labeled ΛΟΓΙΝΟC, "Longinus." Other images in the first millenium will label the sponge-bearer "Stephaton" (example). Mâle explains that these and other pairs of figures flanking the cross represent Ecclesia and Synagoga, the Old and New Testaments (Religious Art, 188-90). In one 13th-century window Ecclesia herself stands left of the cross in a crown and receives the blood of Christ while a dejected Synagoga on the right side turns away blindfolded. Surprisingly, but not without copious reference to the medieval commentators, Mâle argues that Mary and John, the figures most often seen flanking the cross, also represent Ecclesia and Synagoga.

Longinus and Stephaton continue to flank the cross well into the Middle Ages, but from at least the 8th century Mary and John gradually displace them (example). In medieval times Longinus was considered a saint of the Church and was identified with the centurion who had exclaimed, "Truly this man was the Son of God" after the marvels that followed upon Jesus' death. In the high Middle Ages images of the crucifixion will often have the centurion pointing to Jesus on the cross, sometimes with a halo to indicate that he is St. Longinus, as in the Aquileia Crucifixion shown below.

Sometimes Adam will be pictured lying in the soil beneath the foot of the cross or rising from it, owing to a belief that he was buried on Calvary. St. Jerome rejected this idea in the 4th century and other commentators concurrred,4 but it continued to be influential in the art of the Middle Ages. This 13th-century illumination is an example. Four of the 14th- and 15th-century processional crosses studied in Petricioli have Adam sitting up in his sarcophagus and extending his arms pleadingly toward Christ. In a fifth he is standing up in the sarcophagus and has lifted its lid.5 Even as late as this sculpture group from 21st-century New Mexico, Adam and Eve stand together at the foot of the cross, representing the salvation of humanity itself.

When Adam is absent, there may be one or more skulls at the base of the cross, as in the Salimbeni fresco at the top of this page or this example. The skulls refer to the name of Golgotha, where Jesus was crucified, which Matthew 27:33 interprets as "place of the skull." In the Strasbourg Passion Tympanum an entire skeleton is pictured in a sarcophagus at the base of the cross.

Or, in earlier iconography, the foot of the cross may pierce a reclining figure representing Hell. This refers to a 6th-century hymn in which a personified Hell laments that the Cross has pierced his belly and "Adam's race" is pouring out of him. (This link will take you to the hymn and an example of the images it inspired.) On a book cover from Regensburg in the early 11th century (Garrison, plate 6) the cross stabs into the mouth of a great dragon, recalling Isaiah 51:9, "Hast not thou struck the proud one, and wounded the dragon" and the "old serpent" who is defeated in Revelation 12:9 and 20:2.6

In all these examples the artists include some people besides Jesus, and with one exception they are always identifiable persons from the narratives. Thus it is quite dramatic to encounter El Greco's Crucifixion, which pictures him utterly alone.

HIGH MEDIEVAL PATHOS

Writing of French Crucifixions, Mâle claimed that "thirteenth-century artists thought less of stirring the emotions than of recalling the dogma of the Fall and Redemption" (Religious Art, 188). This is true of the images generally, but in literary works on the Crucifixion from late antiquity into the Middle Ages pathos was clearly the intention (Dronke, 190), and as early as the 12th century we start to see it in the art. This fresco in Rome is an example:

As we move into the 13th century the emphasis on pathos begins to take hold. More and more images will present Jesus' body as in the Aquileia fresco or in this image from about 1200, where the head sags onto the chest and there is no collobium.

With the colobium gone, medieval images will reference the liturgical import of the Crucifixion by having figures collect Jesus' blood in chalices. In the Regensburg book cover mentioned above, it is a human figure that holds up the chalice, but thereafter the blood is almost always collected by angels (example). The theology behind the chalice metaphor is expressed in the Glossa Ordinaria on John 19:34 ("one of the soldiers with a spear opened his side, and immediately there came out blood and water"): "It does not say he pierced or he wounded but he opened, for in this way he threw open the gates of life, from which flow out the sacraments of the church, without which there is no entering into life" (V, 1316, my translation).

By the 14th century Crucifixion images tend to pull out all the emotional stops. Giotto's fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel (1303-1305) introduces three details that will become common in the iconography: The Virgin Mary's faint, Mary Magdalene's clutching to the base of the cross, and angels displaying exaggerated gestures. These subsequently appear in Martini's 1333 Crucifixion, which stresses the pathos even more strongly, and in many later examples.

The faint was later woven into Bridget of Sweden's influential vision of the Crucifixion in the latter part of the century7 and, like these other details, persisted for a very long time. But in 1570 Molanus disparaged the faint because John 19:25 says she "stood" by the cross and commentaries on that verse had always taken "stood" to affirm Mary's admirable "constancy of spirit."8 After Molanus Mary is almost always pictured standing, though the faint can be seen even in this altarpiece at the end of the 17th century. Another exception, if indeed it is contemporary with the Baroque works in the church, is this relief in which one of the soldiers mocks Mary for fainting.

The emphasis on pathos reaches its peak in Flemish and German paintings of the 15th century (example). These will add the grossly contorted bodies of the thieves. Instead of treating the wound in Jesus' side as sacramental, they will show the moment when it is pierced by the lance. Many will fill the canvas with thick crowds that press in on the cross.

Other details from Bridget's account also entered the tradition. It was she who specified, in the same chapter, that what Jesus wore on the cross was a tied-up cloth: "He took off his clothes when ordered but covered his private parts with a small cloth. He proceeded to tie it on as though it gave him some consolation to do so." Bridget's witness drove the traditional skirt almost entirely out of the iconography, although it continued to be seen in Hispanic santos (example).

In telling of the soldiers who affixed Jesus to the cross, Bridget goes on to say, "since his left hand could not reach the other corner of the cross, it had to be stretched out at full length. His feet were similarly stretched out to reach the starter holes for the nails.…" This gruesome detail finds it way into the mystery plays at Chester and York, where the soldiers make a grand fuss of tugging and pulling till the limbs reach the holes.9 We do not often see this detail in paintings, but in Corona's large canvas a soldier is stretching the right arm of the thief on the left in preparation for the nail, and in El Greco's Disrobing of Christ a workman prepares one of the starter holes with an awl.

Even the disposition of the feet follows Bridget. In images before her visions, they were often shown side-by-side and nailed separately to the suppedeneum (example). But in the vision Mary says they were arranged "crosswise," and that is how they were portrayed in most subsequent images.

CRUCIFIXION WITH SAINTS

In the 15th and 16th centuries the Crucifixion scene was sometimes attended by saints from later historical eras. The effect is to take Christ's sacrifice out of sequential history into God's timeless presence. Perhaps the most significant example is Fra Angelico's great Crucifixion at the convent of San Marco, Florence, where the usual Crucifixion figures are joined by scores of saints, prophets, and patriarchs. There is less interest in evoking pathos in images of this type (example), perhaps just because of the interest in bringing the event out of historical time.

AFTER THE MIDDLE AGES

In the 16th century and later some Crucifixions became very literal about the violence suffered by Christ's body (example), but for most of the century and beyond artists sought dramatic effect in vivid landscapes, evocative lighting, and other painterly devices. In our own age, with the notable exception of Mel Gibson's Passion of the Christ, violence is eschewed and many artists have preferred stylized portrayals of the crucifixion (example). Some late images also have Mary and John together on one side of the cross rather than flanking it (example). This appears to be a reference to John 19:26-27 – "When Jesus…had seen his mother and the disciple standing whom he loved, he saith to his mother: Woman, behold thy son. After that, he saith to the disciple: Behold thy mother. And from that hour, the disciple took her to his own."

Prepared in 2016 by Richard Stracke, Emeritus Professor of English, Augusta University.

HOME PAGE

MORE IMAGES

- Early 9th century: A Byzantine reliquary lid with Christ in the collobium and very much alive.

- Circa 1100: Below the cross in an ivory plaque of the Crucifixion is an image of Adam being buried by his sons.

- 12th or 13th century: Apse mosaic in Rome.

- 12th or 13th century: A window in Canterbury surrounds an image of the Crucifixion with four events from the Old Testament that were believed to prefigure it.

- 1160-1180: The Crucifixion is the ninth of the ten panels outlining the Life of Christ on a German portable altar.

- Circa 1200: This Crucifixion mosaic in St. Mark's, Venice, has Adam's skull and most of the persons mentioned in the gospel accounts.

- Early 13th century: A carved Crucifixion group in South Tyrol, Italy.

- 13th century: This 13th century fresco from Istria (Croatia) closely follows the pattern seen first in the sarcophagi and then in the Eastern icons. Western images continue to use this pattern into the present day. See the description page.

- Mid-13th century: In this Croatian tympanum relief has features of the older style emphasizing Christ's divinity and the newer style that emphasizes his (suffering) humanity.

- 1265-68: The Crucifixion panel on Nicola Pisano's pulpit for Siena Cathedral is an example of including Ecclesia and Synagoga in the scene.

- 1280-85: The Crucifixion is the central image in The central tympanum on the west façade of Strasbourg Cathedral.

- 1285: In Jacopino da Reggio's Crucifixion with St. Francis it is St. Francis, not Mary Magdalene, who hugs the cross.

- 1300: This stained glass is an early example of the growing pathos in Crucifixions.

- Early 14th century (Ethiopia): The presence of Christ expressed only symbolically by a jeweled cross in a Crucifixion scene from an Ethiopian gospel book.

- Circa 1310-31: Detail from the reliefs on the façade of Orvieto Cathedral.

- 1320-25: The Crucifixion is figured on the right leaf of Jacopo del Casentino's Madonna and Child Enthroned triptych.

- 1350: This panel has an early example of Mary's faint.

- Circa 1400: Detail from a Spanish altarpiece.

- 15th century: Fra Angelico with Mary's faint. Longinus and Stephaton are mere onlookers on the left.

- 1416: The Salimbens' enormous fresco of the Crucifixion, with Mary's faint and a multitude of other details.

- 1440s: Fra Angelico's fresco of St. Peter Martyr adoring the Cross, in a friar's cell in San Marco, Florence.

- 16th century: Fainting in Corona's Crucifixion, Mary seems to fall toward the viewer.

- 1512-31: Sculpture group in the main retable of Oviedo Cathedral.

- 1515-25: Van Orley's Crucifixion with the souls awaiting redemption.

- 1565: Tintoretto's painting strongly emphasize Mary's faint.

- 1683: Villalpando's grand canvas, Moses and the Brazen Serpent and the Transfiguration of Jesus, relates the Crucifixion to the bronze serpent episode in Numbers 21 – and both of those to the Transfiguration.

- 1690-1720: A carving with Mary's faint derided by a grimacing soldier.

- 18th or 19th century: Sculpture group with cannons at Meersburg Castle, Germany.

- 19th century: Relief, Mary and John gaze in awe at the crucified Christ.

- 19th century: In Sebastiano Santi's Crucifixion with Saints Saints Augustine, Cajetan, Anthony of Padua, and Lorenzo Giustiniani contemplate Christ on the cross.

- 1875: An altarpiece in Montreal surrounds the usual Crucifixion scene with Old Testament episodes believed to prefigure it.

- Undated: Mary holds a scapular in this image in a Venice church.

- Undated: The Precious Blood of Christ symbolically relates the Crucifixion to the Eucharist, to Purgatory, and to the doctrine of the Trinity – not to mention the welcoming of the Good Thief into Heaven.

- Undated: The device of picturing an angel collecting Christ's blood in a chalice is adapted to a painted panel in a Venetian chapel announcing the presence of a vial of Christ's blood.

IMAGES PUBLISHED IN BOOKS

- 1457: "Calvary," a woodcut in a German missal, follows iconography typical for this era and region. The thieves' arms are pulled back over the horizontal of T-crosses, an angel arriving to take Dismas on the left and a devil taking Gestas on the right Fainting Mary, held up by St. John. Blood flows from the five wounds, but not into any cup. In the left foreground Mary faints and John holds her up while Mary Magdalene hugs the cross and looks up at Jesus. In the right foreground a man richly clad holds hand to beard in a pensive pose while another in military garb addresses him. Published in Strauss, LXXX, 9-10.

ALSO SEE

- The Death of Jesus

- Crosses and Crucifixes

- Ecclesia: The Church

- St. Mary Magdalene

- St. Longinus

- St. Bridget of Sweden

TEXTS

- Matthew 27:33-58, Mark 15:22-41, Luke 23:26-49, John 19:16-37

- The Gospel of Nicodemus (also known as Acts of Pilate)

- Golden Legend #53: html or pdf

- The Prophecies and Revelations of Saint Bridget of Sweden

NOTES

1 For Jesus' priesthood see practically any chapter in Hebrews, and especially 5:10, which says he was "called by God a high priest according to the order of Melchisedech." For the continuity between the events on Calvary and the liturgy, see for example Justin Martyr's assertion of circa 155: "In like manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh" (First Apology, lxvi). This understanding of the liturgy arises from the institution narratives in Matthew 26:26-28, Mark 14:22-24, and Luke 22:19-20 and from "Bread of Life" discourse in John 6:22-59. In I Corinthians 11:23-26 Paul writes of having "received of the Lord" the same institution narrative and "delivered" it to the faithful in Corinth. He concludes that "as often as you shall eat this bread, and drink the chalice, you shall shew the death of the Lord, until he come."

2 Schiller (II: 5, 109) argues that the sun and moon in such images "refer to the cosmic sovereignty of Christ and his eternal reign," citing the way the symbols had been used in Roman art. Other scholars have suggested that they refer to the darkness that fell when Christ died or to Ecclesia and Synagoga: See Mark 15:33, Luke 23:34, and Savage, "Iconography of Darkness."

3 The evangelists give differing accounts regarding what was on the sponge. In Matthew 27:34 it was a mix of wine and gall. Mark says it was myrrhatum vinum (wine mixed with myrrh?). Luke and John both say it was vinegar.

4 Jerome, Commentary on Matthew, IV, xxvii, 33. Writers cited in the Glossa Ordinaria (V, 455) concur in Jerome's judgment, as does the Golden Legend (Ryan, I, 209).

5 Exposition Permanente d'Art Sacré à Zadar, 39-50. The processional crosses are all from parish churches near Zadar and all from a Zadar workshop. Verious media, all gilded.

6 Two other Ottonian Crucifixion images published in Garrison put the serpent below the cross or coiling around its base: a "Mathilde Cross" in Essen Cathedral (figure 33) and the cover of the "Regensburg Sacramentary" (figure 48).

7 Prophecies and Revelations,

I, 10.

8 Molanus, Historia SS. Imaginum, 444-46.

9 Deimling, II, 303-304 (Play XVI, 545-80); Beadle, 214-15 (Crucifixion, 73-100).