The Council did not extend this reasoning to the Father or the Holy Spirit.3 However, from the late Middle Ages forward we see images of the Father alone presiding over Annunciation images (example), altarpieces (example), etc.

THE HOSPITALITY OF ABRAHAM

Genesis 18:1-2 says that when "the Lord" (singular) visited Abraham at Mamre the latter looked up and saw three men approaching. As the chapter goes on it continues to alternate between singular and plural. Most Christian writers took this to refer to the Trinity.4 For Christian artists, the story provided a neat solution to the problem of representing the Godhead. By picturing what was visible to Abraham they could direct the viewer's mind to the invisible reality of God's presence at Mamre.

Early images of the Hospitality of Abraham emphasize the divinity represented by Abraham's visitors by picturing him as bowing to them in adoration and bringing forth what was in effect a burnt offering. In a mosaic panel from the 5th century the visitors radiate light in the upper register and are set against a gold background in the lower. The mosaic shown at the top of this page, from the 6th century, emphasizes the sacrificial character of the roasted calf that Abraham offers on the left by parallelism with Isaac and the ram, the sacrificial victims on the right.

Offering such a strong yet subtle way of calling the Triune God to the onlooker's mind without suggesting that he can be seen with mortal eyes, the Hospitality of Abraham has continued to be the Eastern churches' primary way of presenting the Trinity. In later centuries the three men were often shown as angels with wings (example), a choice most likely due to a desire to obviate any thought that the three figures represent the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit individually. On the other hand, in this carving from the 18th century only one angel addresses Abraham and Sarah.

An influential icon by Andrei Rublev in 1410 drastically reduces the elements in the Hospitality of Abraham. Abraham, Sarah, and the calf are gone, leaving only the three angels, the table, and a softly rendered tabernaculum in the background.

THE THRONE OF MERCY

Three new ways of representing the Trinity developed in the West in the Middle Ages. Each breaks with the taboo on portraying the Father, but two of them do so on the basis of scriptural authority.

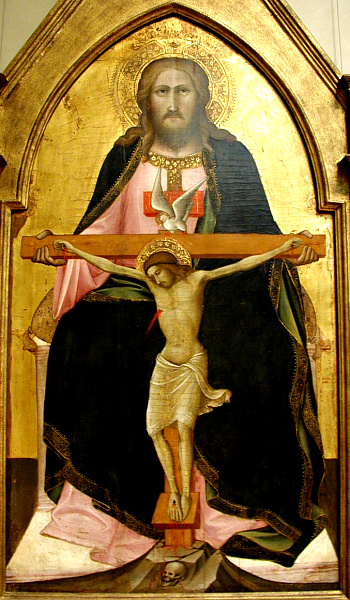

The first is the Throne of Mercy, which visualizes John 3:16, "God so loved the world, as to give his only begotten Son; that whosoever believeth in him, may not perish, but may have life everlasting." In this iconographic type the Father presents his dying Son on the cross to the viewer. A dove sits atop the cross to represent the Holy Spirit. The basis for this symbolism is that when Jesus was baptized he "saw the Spirit of God descending as a dove" (Matthew 3:16, c.f. Mark 1:10, Luke 3:22, John 1:32). Beneath the cross, the "world" that will gain "eternal life" is represented by either a small model of Golgotha with Adam's skull, as in the first picture on the right, or a mappa mundi orb (as in this example). In some painted versions the Trinity is flanked by Mary and John (example) or by the hosts of Heaven (example).

The earliest example I have seen so far is in a manuscript illumination from the beginning of the 13th century, but it has antecedents in which a roundel with an image of the Son is placed over the chest of the Virgin Mary or of the Father. These relate, respectively, to the virgin birth or to John 1:1 ("In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God").5

In 15th century works the The Throne of Mercy is sometimes merged with other iconographic types, for example with the Crucifixion and Death of Jesus in this example or with the Annunciation in this one. In a Spanish altarpiece of the period it mediates between an upper panel representing the Crucifixion and a lower one depicting St. Michael's victory over Satan. At the beginning of the next century, Quentin Massys put a panel pairing the Trinity with the Madonna in the center of an altarpiece.

One interesting variant from the 19th century introduces a note of exuberance to the type while breaking out of the plane of the painting.

THREE IDENTICAL MEN

The earliest known image of the Trinity is in a 4th-century sarcophagus frontal. Three very similar men, one of them seated on a throne, are creating Eve from Adam. The Trinity is also represented as three men in 15th-century images of the decision to redeem mankind through the Son's self-sacrifice and to send the angel to the Virgin Mary.6 Then in the late 15th and early 16th centuries we start to see the three represented as identical in appearance, as in this miniature and another in the Hours of Henry VIII (Wieck, 135), both of them illustrating prayers for Trinity Sunday. The picturing of three identical men gained currency, especially in areas colonized by Spain and in images of the Coronation of Mary (example). In these late examples the three men are identical in appearance. In 1745 Benedict XIV pronounced this way of picturing the Trinity "not absurd" because it might be said to refer to Abraham's three visitors, but this faint praise did not save it from going out of favor.8

In the same document, however, the pope roundly condemned a related iconographic type: a single human figure with three faces. The earliest example I have seen is a 13th-century fresco from Perugia. In the 14th, Filippo Lippi pictured the Trinity as a disembodied head with three faces. Even before Benedict XIV this type had been attacked in the 16th century by Molanus and forbidden in the 17th by Urban VIII.7 There is also a Coronation of the Virgin from the 15th century that pictures the Holy Spirit as a dove but the Father and Son as identical figures.

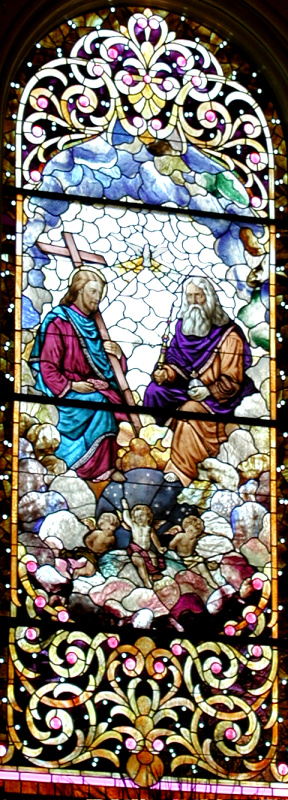

THE SON SITTING AT THE RIGHT HAND OF THE FATHER

Perhaps the Trinity image most often seen today is the one that seats the Son with a cross at the right hand of the Father, with the Holy Spirit between them as a dove emitting light rays, as in the third picture at right. Placing the Son at the Father's right hand responds to a rich vein of scriptural references.9 The earliest examples of this type that I have seen are a miniature in a missal dated 1490-1500 (Wieck, 40) and Marco Moro's 16th-century Trinity and All Saints in the Ognissanti in Venice. Like almost all subsequent exemplars it makes the Father an old man with a beard, a choice that could be explained by the reference to God as "the Ancient of Days" in Daniel 7:9, 13, 22 and in Revelation 1:14 as having hair "as white … as snow." He almost always holds a mappa mundi orb, symbol of his universal sovereignty, in his left hand.

When this iconographic type is merged with other subjects, as it often is, the cross is usually absent, as in this apotheosis of St. Anthony in the dome of a chapel in Ravenna, this Assumption in Mexico, and this Vision of St. Stephen in San Moisè, Venice.

In Orthodox versions the Son holds a book open to the viewer. A geometrical frame will close off the image of the dove from the Father and Son figures (example), perhaps emphasizing Orthodox objections to the Latin formulation of the Nicene Creed, which says the Holy Spirit "proceeds from the Father and the Son."

ABSTRACT SYMBOLS

Various symbols have been devised to express the trinite and invisible God, such as a triangle within a circle, the "Trinity shield," and the Tetragrammaton in a triangle. In Eastern churches after the Council of 1156 the Hetoimasia or "Prepared Throne" symbol was installed in proximity to the altar. This symbol had a throne to represent the Father, a dove for the Holy Spirit, and for the Son a book and a selection of instruments used in his Passion – the spear, the nails, the sponge, etc. The original purpose of this symbol was to emphasize the teaching that Christ's redemption of mankind through the Cross was predestined from all time. The Council proposed placing it near altars in order to emphasize a second doctrine that it affirmed: that in the Eucharistic liturgy, Christ's sacrifice is offered to the entire Trinity, not just to the Father and Holy Spirit as some had suggested.10

Prepared in 2015 by Richard Stracke, Emeritus Professor of English, Augusta University. Revised 2016-09-17, 2017-02-01, 2018-09-19, 2020-08-06.

HOME PAGE

The Trinity in a 6th-century Hospitality of Abraham mosaic: Detail from the north wall of the chancel at the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna

The Throne of Mercy – See description page

Trinity with the Son "seated at the right hand of the Father" – See description page

MORE IMAGES

- 325-75: A detail in a dome painting in Egypt pictures the Hospitality of Abraham.

- Circa 1300: a miniature Throne of Mercy inside a "Vierge Ouvrante."

- 14th century: A manuscript illumination of the "Throne of Mercy" type in which Mary shares the throne with the Father.

- 16th century: a stone relief in Burgos Cathedral is an early example of placing the Son at the Father's right, with the dove between them.

- Late 16th century: At the apex of Saraceni's Paradise the Son sits beside the Father but without a cross.

- 17th century?: A "Hospitality of Abraham" fresco in Padua.

- 17th or 18th century: Painting of Moses and Aaron worshiping the Trinity.

- 1637: Murillo's Abraham and the Three Angels pictures the three as men, not as angels.

- 1696-1700: Sculpture of the Trinity atop the Trinity Altarpiece in the Gesù, Rome.

- Early 18th century: Two frescos of the Hospitality of Abraham.

- First quarter, 18th century: In Pellegrini's Trinity with SS. Joseph and Francis di Paola St. Joseph's portrait echoes that of the Father above.

- 18th century: Relief with a Dominican saint worshiping the Trinity.

- 18th century: A Greek triptych where Christ holds a book and the dove is closed off in a roundel.

- 1753: A Mexican nun's badge that combines Coronation and Immaculate Conception iconography.

- Second half of the 18th century: A Mexican nun's badge of the Annunciation with a Trinity composed of three identical men.

- 19th century: Near Pamplona, Spain, a carved altarpiece– Son at Father's right, Spirit above.

- Undated: From South Tyrol, a Trinity sculpture with Father and Son seated in Heaven and the dove between them.

- Undated: Pentecost sculpture with the Son at the Father's right hand, both together sending down the Holy Spirit.

DATES

- In Eastern churches Trinity Sunday is the Sunday of Pentecost.

ALSO SEE

- The Baptism of Christ

- The Coronation of the Virgin

- Molanus, I, iii-iv (32-38) discusses the diverse opinions of theologians regarding how or whether the divine is to be represented in pictures.

NOTES

1 Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. "Trinity."

2 Exodus 20:4-5, "Thou shalt not make to thyself a graven thing, nor the likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath, nor of those things that are in the waters under the earth. Thou shalt not adore them, nor serve them." Isaiah 40:18, "To whom then have you likened God? or what image will you make for him?" Acts 17:29, "We must not suppose the divinity to be like unto gold, or silver, or stone, the graving of art, and device of man."

3 See the "Definitions" of the Second Council of Nicea.

4 See for example Augustine, On the Trinity, II, 10-11; Isidore, Allegoriae, §21 and note; Molanus, 35. The Glossa Ordinaria (I, 230-31) notes the opinion in a Greek source that the three men represent Jesus Christ accompanied by Moses and Elijah but then goes on to cite Ambrose, Augustine, Cyril of Jerusalem, and Gregory the Great for the traditional interpretation.

5 Schiller, I, 7-8 and figs. 1-4.

6 Schilller, I, 9-12 and figures 12, 14, 16.

7 See the bull Sollicitudine Nostrae and Panofsky, "Once More," 433 n. 66.

8 Molanus, 37. Panofsky, ibid. The tradition does survive into the 19th century in Mexico. See Zarur and Lowell, figures 132-34, 141.

9 In Christian thought the notion of the Son sitting in Heaven at the right hand of the Father starts with Psalm 109:1, "The Lord said to my Lord: Sit thou at my right hand: Until I make thy enemies thy footstool." In the Gospels Jesus refers this verse to himself (Mt 22:44, Mk 12:6, Lk 20:42), as does Hebrews 1:13. At the end of Mark's Gospel (16:19), "the Lord Jesus, after he had spoken to them, was taken up into Heaven, and sitteth on the right hand of God" as Jesus had prophesied by during his trial (Matthew 26:64, Mark 14:62, Luke 22:69). After the Ascension, St. Stephen's great speech to the Jews concludes with "Behold, I see the heavens opened, and the Son of man standing on the right hand of God" (Acts 7:55). This way of imagining the Son is also adopted by St. Paul in Romans 8:34, Ephesians 1:20, Colossians 3:1 – and by 1 Peter 3:22 and Hebrews 1:3, 8:1, 10:12. The Nicene Creed also asserts that Christ "ascended into Heaven, sits at the right hand of the Father, and shall come again in glory" (Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v. "Nicene Creed").

10 Milliner, 88.