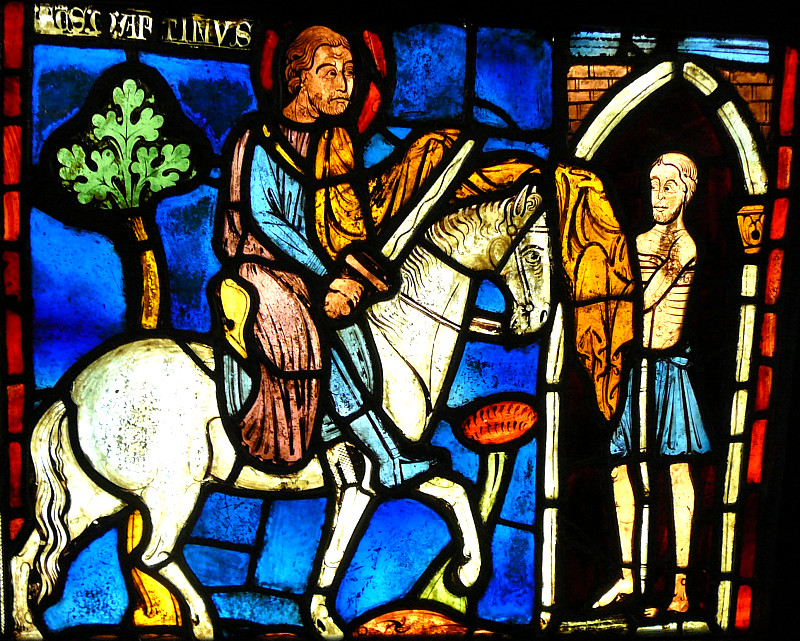

This is essentially a narrative image but sometimes the horse is absent and the beggar functions essentially as an attribute (example). The story comes from Sulpicius Severus' 5th-century life of the saint and was part of the Golden Legend's account in the 13th century. The next part of the story is Martin's dream that night, in which he sees Christ wearing the half-cloak and telling the angels, "Martin, yet new in the faith, hath covered me with this vesture" (image).

OTHER NARRATIVE IMAGES

Because St. Martin's fame was so widespread visitors may find other narrative images from the Legend in churches and museums. One popular subject was Martin's renunciation of arms (example). Even more popular were his resurrections of various young persons (example). At his death, both St. Severus and St. Ambrose were granted visions of the angels welcoming him into Heaven with song (example with Severus, example with Ambrose).OTHER PORTRAIT TYPES

On the strength of the story of Martin's welcome into Heaven, he is often portrayed in the clouds accompanied by angels, as in the third picture at right.In that picture the saint is also accompanied by a goose. Duchet-Suchaux (232) explains that the goose is traditional fare on St. Martin's day. Bataillard adds that in the early middle ages a fast for Advent began on November 12. Although it later fell into desuetude, anticipatory feasting on November 11 continued to be observed. It went by the name of Martinalia, and commemorative coins featuring the goose were even struck for the celebration. As for why the goose became the characteristic feature of the feast, Bataillard suggests that it was "for the [ancient] Gauls and in the Middle Ages the largest and most esteemed of the birds in the barnyard." In Part Two of Don Quixote (1615), it appears to be pigs that are slaughtered in the Martin's Day feasts. Quixote says of an unauthorized biography, "I have heard of this book…and verily and on my conscience I thought it had been by this time burned to ashes as a meddlesome intruder; but its Martinmas will come to it as it does to every pig" (II, lxii).

For preaching in Illyria against the Arians Martin was publicly scourged and driven back to Italy (Sulpicius Severus, vi ¶2), so in the 6th century when Catholics took over the basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo from the Arians in Ravenna, they put his portrait at the head of the procession of martyrs in the nave. In succeeding centuries he is sometimes portrayed with one or two fingers pointing up (examples with one finger and with two). This could possibly be a reference to his teachings, against the Arians, regarding the nature of Christ.

Throughout his career Jacopo Bassano consistently paired St. Martin with St. Anthony Abbot. In 1542 the two flank the Madonna,1 in 1568 they are in the lower left of the Adoration of the Shepherds, in 1578 in the lower right of the Paradiso, and in the 1580s in St. Martin and the Poor Man with St. Anthony Abbot. Most likely this pairing was intended to reflect the "active" and "contemplative" ways of living the gospel, which were first distinguished by Gregory the Great in the 6th century and later became a common medieval trope.2

St. Martin was born in Pannonia, the forerunner of medieval and modern Hungary. Consequently he is sometimes included in Hungarian group portraits of saints (example).

Today in Italy and some other parts of Europe people observe St. Martin's feast day by baking or buying "St. Martin cookies" (example).

Prepared in 2014 by Richard Stracke, Emeritus Professor of English, Augusta University. Revised 2016-09-12,27; 2016-10-29; 2016-11-28, 2018-01-19.

HOME PAGE

13th-century stained glass (See description page)

16th-century statuette in Croatia (See description page)

St. Martin with the goose and other attributes (See description page)

ATTRIBUTES

- Goose

- Cloak

MORE IMAGES

- 6th-8th century: The apse mosaic in the Ambrosian Basilica in Milan illustrates the legend of St. Ambrose's vision of the death of St. Martin.

- Medieval: Predella panel: Martin as Byzantine military officer.

- 1344: Detail from Guariento di Arpo's Coronation of the Virgin altarpiece.

- Early 15th century: A goose features prominently in this portrait of St. Martin in his episcopal vestments.

- 1430-35: Embroidered roundels with scenes from St. Martin's life.

- 1474: Fresco in Beram, Croatia.

- 1580s: Jacopo Bassano's St. Martin and the Poor Man with St. Anthony Abbot pairs Martin the soldier with Anthony the hermit, exemplifying the active and contemplative lives.

- 18th century: Giambattista Tiepolo's portrait of St. Martin and an acolyte has no attributes identifying the saint.

DATES

- Feast day: November 11

- Lived from 316 to 397

BIOGRAPHY

- Golden Legend #166: html or pdf.

- Sulpicius Severus, On the Life of St. Martin.

- Roman Breviary, IV, 734-35 (1632 Latin text: 1095-1100).

- Gregory of Tours, De Gloria Confessorum / Glory of the Confessors, chapters 4-14 (Migne, 832-38; van Dam, 5-13).

- "De Cultu S. Martini." Analecta Bollandiana III, 217-57.

- Guibert of Gembloux, "Carmina de Sancto Martino." Ed. Hippolyte Delehaye. Analecta Bollandiana VII, 302-20.

ALSO SEE

NOTES

1 "Virgin and Child with the Saints Martin of Tours and Anthony the Great" (1542-43). The painting is in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich. A photograph is available at this page on Wikimedia Commons (retrieved 2022-06-11).

2 Gregory explains what constitute the active and contemplative lives in his Homilies on Ezekiel, II, ii, 7-8 (Migne, Pat. Lat. LXXVI, 952-57). There is a new English translation of the homilies (Etna, California: Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies, 1990), but I have not yet read it. The subject is also studied in Aquinas's Summa Theologiae, Second part of Part II, questions 179-182. Online at this page at New Advent. For a history of the concept, see Sister Mary Elizabeth Mason, Active Life and Contemplative Life: A Study of the Concepts from Plato to the Present (Online at Marquette University Press Publications, 1961).